Mongolia’s wide-open steppes, mountain passes and river valleys hold layers of history from nomadic empires to Silk Road traders. Walking those landscapes, you encounter temples, tombs and rock art that tell how people adapted to a harsh, changing environment.

There are 23 Historical Places in Mongolia, ranging from Amarbayasgalant Monastery to Uushgiin Uver Archaeological Site. For each entry, you’ll find below Location (province / nearest city / coords if remote),Period (era or century / year),Why notable (max 15 words). This list is meant to orient travelers and researchers alike, and you’ll find below.

How were the sites on this list chosen?

The list groups well-documented archaeological sites, monasteries and monuments that are referenced in scholarship or heritage registers, prioritizing diversity of period, region and cultural significance so readers get a broad, research-friendly overview.

When is the best time to visit these places?

Most sites are easiest to reach late spring through early autumn when roads are passable; check local conditions, guided-visit availability and any seasonal closures before planning a trip.

Historical Places in Mongolia

| Name | Location (province / nearest city / coords if remote) | Period (era or century / year) | Why notable (max 15 words) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape | Övörkhangai & Arkhangai / Kharkhorin / 48.20N,102.48E | 6th–13th century | UNESCO cultural landscape with monuments of nomadic empires |

| Erdene Zuu Monastery | Övörkhangai / Kharkhorin | 16th century | Mongolia’s earliest surviving Buddhist monastery, built at Karakorum |

| Karakorum | Övörkhangai / Kharkhorin | 13th century (founded 1220s) | Capital of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century |

| Petroglyphic Complexes of the Mongolian Altai | Bayan-Ölgii & Khovd / Altai Mountains / 48.60N,88.00E | Bronze Age–Medieval | UNESCO-listed rock art and deer stone ensemble |

| Amarbayasgalant Monastery | Selenge / Erdenebulgan | 18th century (1736–1745) | One of Mongolia’s largest surviving 18th-century monasteries |

| Gandantegchinlen Monastery (Gandan) | Ulaanbaatar / City center | 19th century | National monastery housing a monumental Buddha and active clergy |

| Choijin Lama Temple Museum | Ulaanbaatar / City center | Early 20th century (1904) | Well-preserved temple complex with thangka and ritual collections |

| Bogd Khan Palace (Winter Palace) | Ulaanbaatar / City center | Late 19th–early 20th century | Winter residence of Mongolia’s last monarch; royal artifacts museum |

| Manzushir Monastery ruins | Töv / Bogd Khan Mountain / 47.95N,106.70E | 18th century | Important monastery destroyed in 1930s; notable ruins and museum |

| Ongi Monastery (Ongiin Khiid) | Ömnögovi / near Saikhan-Ovoo | 17th century | Ruined twin monastery complex on Ongi River, destroyed during purges |

| Tövkhon Monastery | Arkhangai / Shireet Uul | 17th century (founded 1653) | Zanabazar’s mountain retreat and artistic, spiritual center |

| Shankh Monastery (Shankhyn Khiid) | Övörkhangai / Shankh | 17th century | One of Mongolia’s oldest monasteries with historic collections |

| Khamar Monastery (Khamariin Khiid) | Khentii / Kherlen | 19th century | Remote monastery in a gorge; significant Khentii religious site |

| Uliastai Fortress (Old Uliastai) | Zavkhan / Uliastai | 18th century | Qing-era military and administrative garrison town with historic buildings |

| Khovd Historic Town | Khovd / Khovd city | 17th–19th century | Multiethnic frontier city with Qing-era quarters and Silk Road links |

| Deer Stones | Nationwide (notably Orkhon and Altai) | Late Bronze Age–Early Iron Age | Carved standing stones with deer motifs; ritual and funerary markers |

| Khogno Khan Monastery ruins | Övörkhangai / Kharkhorin | 17th century | Scenic mountain monastery ruins near Kharkhorin |

| Tsetserleg Monastic Complex | Arkhangai / Tsetserleg | 18th–19th century | Historic Buddhist center around which the town developed |

| Ikh Khorig (Nomadic royal preserves — archaeological zones) | Övörkhangai / Orkhon Valley area / 48.10N,102.40E | 6th–13th century | Restricted imperial burial and ceremonial zones associated with steppe rulers |

| Uushgiin Uver Archaeological Site | Arkhangai / near Bayankhongor border / 46.00N,100.50E | Bronze Age | Stone burial mounds and associated Bronze Age artifacts |

| Karakorum Museum (Kharkhorin Museum) | Övörkhangai / Kharkhorin | 20th century (museum preserving ancient finds) | Houses artifacts and exhibits interpreting Karakorum and regional archaeology |

| Kharkhorin Monastic Ensemble (other ruins) | Övörkhangai / Kharkhorin | 16th–18th century | Surviving monastic ruins and secondary temples near Erdene Zuu |

| Tamsagbulag Burial Mounds (notable kurgans) | Central Mongolia / near Nalaikh / 2 locations coords 47.90N,107.40E | Iron Age–Medieval | Prominent burial mounds (kurgans) demonstrating steppe funerary practices |

Images and Descriptions

Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape

Register this valley as Mongolia’s heartland of nomadic empires. It holds tombs, inscriptions and ruins from Turkic, Uyghur and Mongol eras. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site that shows long-term nomadic life along the Orkhon River. It anchors the list as the richest linked landscape of Mongolian history.

Erdene Zuu Monastery

Name this one of Mongolia’s oldest surviving Buddhist monasteries near Karakorum. It dates to the 16th century and incorporates stones from the old capital. It remains an active religious site and a key example of post-imperial Buddhist revival. It shows how sacred and imperial histories overlap.

Karakorum

Identify Karakorum as the 13th-century capital of the Mongol Empire. It contains archaeological remains of palaces, administrative buildings and workshops. It marks the political center of early Mongol statecraft and trade connections. The site links directly to Erdene Zuu and the Orkhon Valley story.

Petroglyphic Complexes of the Mongolian Altai

Record these rock-carved images as prehistoric and historic art across the Altai mountains. They feature hunting scenes, animals and ritual symbols from Bronze Age to medieval times. They are a UNESCO World Heritage property that shows long human use of high mountain zones. They add deep time and visual culture to the list.

Amarbayasgalant Monastery

Describe this monastery as a large 18th-century Buddhist complex in northern Mongolia. It is known for fine architecture and careful restoration after 20th-century destruction. It served as a major religious and cultural center for centuries. It represents the scale of classical Mongolian monastic life.

Gandantegchinlen Monastery (Gandan)

Note this monastery as Ulaanbaatar’s main active Buddhist center. It dates to the 19th century and hosts large statues and regular ceremonies. It survived political purges and remains a living religious institution. It shows the continuity of Buddhism in modern Mongolia.

Choijin Lama Temple Museum

List this Ulaanbaatar temple complex as an early 20th-century religious site turned museum. It preserves exquisite ritual art, thangka paintings and ceremonial objects. It survived the 1930s purges and offers a close view of premodern monastic life. It is compact and easy to access in the capital.

Bogd Khan Palace (Winter Palace)

Identify this palace as the former residence of the last monarch, the Bogd Khan. It dates to the early 20th century and houses royal collections and religious relics. It now functions as a museum that shows the link between monarchy and religion. It provides urban historical context for modern Mongolia.

Manzushir Monastery ruins

Record these ruins in a scenic valley near Ulaanbaatar as the remains of a major 18th-century monastery. The complex was largely destroyed during 20th-century anti-religious campaigns. Today it offers ruins, a museum and a memorial to lost monastic culture. It stands as evidence of both spiritual importance and historical rupture.

Ongi Monastery (Ongiin Khiid)

Describe Ongi as a riverside monastery complex that once ranked among the largest in Mongolia. It suffered heavy destruction in the 1930s and now shows surviving temples and scattered ruins. Local groups have restored parts and hold ceremonies. It illustrates the scale of provincial monastic networks.

Tövkhon Monastery

Name this mountaintop hermitage as a small, remote monastery founded in the 17th century. It served as a retreat for important religious leaders and artists. It sits on a ridge with panoramic views and preserved ritual objects. It represents the solitary, creative side of Mongolian religious life.

Shankh Monastery (Shankhyn Khiid)

List Shankh as one of Mongolia’s old monastic sites dating to the 17th century. It played a regional religious role and hosted important lineages. It contains temples, steles and historic artifacts where preserved. It adds regional depth to the map of monastic history.

Khamar Monastery (Khamariin Khiid)

Describe Khamar as a scenic monastery set in a river valley and mountain landscape. It dates from the 18th–19th centuries and was known for teachings and ritual arts. It experienced destruction and later partial restoration. It demonstrates how geography shaped monastic placement.

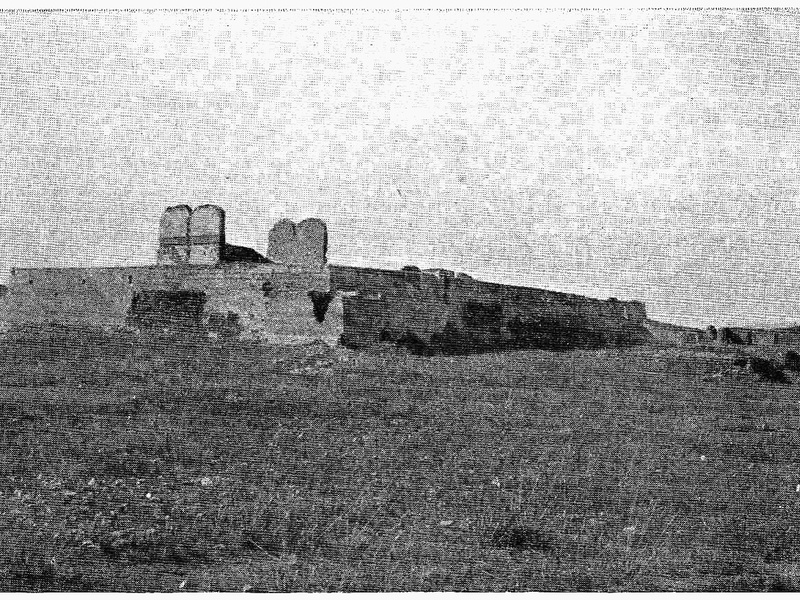

Uliastai Fortress (Old Uliastai)

Record this fortress town as a Qing-era administrative and garrison center from the 18th–19th centuries. It functioned as a border post and regional capital under the Qing. Surviving structures and layout reflect imperial military presence in western Mongolia. It adds a colonial-administration layer to the list.

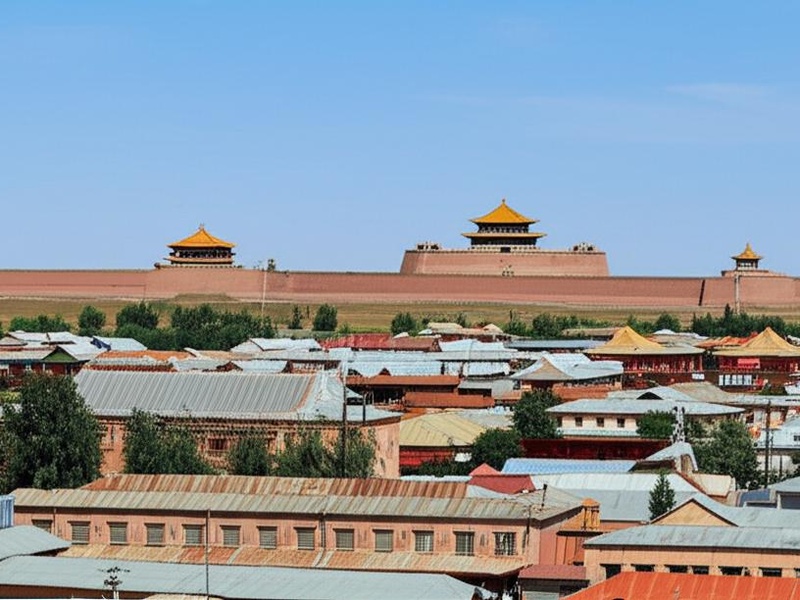

Khovd Historic Town

Name Khovd as a multicultural frontier town in western Mongolia with long trading history. It retains Russian, Tibetan and local architectural influences. It served as an important caravan and administrative hub for the region. It shows Mongolia’s ethnic and commercial diversity.

Deer Stones

Describe deer stones as Bronze Age standing stones carved with deer and other symbols. They appear across northern and central Mongolia and date to about 1200–700 BCE. They represent the earliest monumental art of the steppe and ritual beliefs. They provide links to prehistoric nomadic identity.

Khogno Khan Monastery ruins

Record these ruins near the Khogno Khan mountain as the remains of a 17th–19th-century monastery. The site sits in a protected forest and offers visible foundations, scattered stones and a quiet setting. It connects natural sacred landscapes with monastic history. It is often paired with nearby dunes and rock formations.

Tsetserleg Monastic Complex

List Tsetserleg’s complex as the main religious center of the Arkhangai region. It dates to the 17th–18th centuries and includes temples, courtyards and monastic halls. It served both local and wider religious networks. It illustrates a town-scale monastic presence outside the capital.

Ikh Khorig (Nomadic royal preserves — archaeological zones)

Name Ikh Khorig as the sacred royal hunting preserve tied to early steppe elites. It was historically restricted and holds graves, fortifications and ritual sites. The area is archaeologically sensitive and often protected. It connects living landscapes to elite nomadic practices.

Uushgiin Uver Archaeological Site

Describe Uushgiin Uver as a prehistoric burial cave with rock art and grave goods. It dates to the Bronze and Iron Ages and contains human remains and artifacts. Archaeologists use it to study early pastoral societies in Mongolia. It adds prehistoric funerary evidence to the list.

Karakorum Museum (Kharkhorin Museum)

Record this local museum as the main repository for finds from Karakorum and the Orkhon Valley. It displays pottery, coins, tools and explanatory panels about the ancient capital. It helps connect field ruins to material culture. It is an essential stop for context after visiting nearby sites.

Kharkhorin Monastic Ensemble (other ruins)

List these scattered ruins around Kharkhorin as the remains of multiple temples and monastic buildings. They date from post-imperial Buddhist expansion and later decline. The ensemble shows how religious complexes grew around the old capital. They complement Erdene Zuu and the wider archaeological landscape.

Tamsagbulag Burial Mounds (notable kurgans)

Describe these burial mounds as prominent kurgans from Bronze and Iron Age societies. They contain earth and stone tumuli with burial goods and occasional horse remains. They reveal elite burial customs and steppe mobility. They provide clear physical evidence of prehistoric social hierarchy.