8 Most Dangerous Cities in Guinea-Bissau

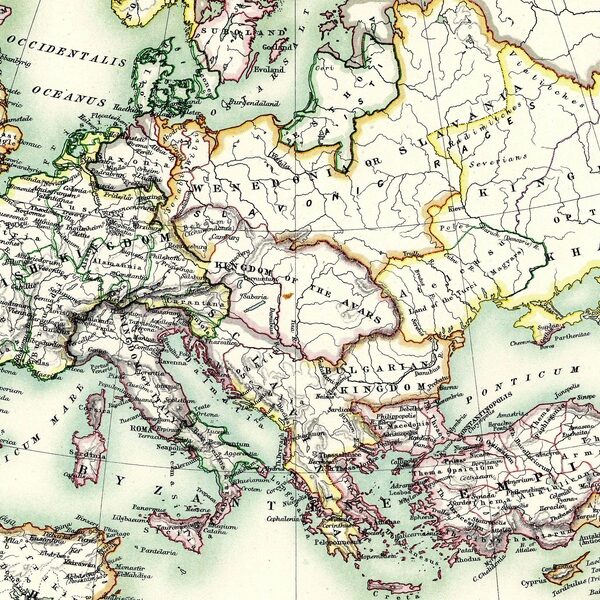

The run-up to and aftermath of the 2012 military coup left vivid scenes on Bissau’s streets — burning tires, roadblocks and armed factions contesting authority — and those moments helped accelerate a trend that would make parts of the country into routes for illicit trade. By the 2010s UNODC investigators and regional press were increasingly describing Guinea-Bissau as a trans-shipment point for cocaine bound for Europe, a change that reshaped local criminal dynamics and raised the stakes for towns across the country (UNODC).

These patterns matter to travelers, aid workers and residents: institutions that once handled disputes now struggle with corruption and capacity, markets and transport routes attract armed groups, and coastal and river towns see small-boat trafficking that can provoke violent reprisals. Guinea-Bissau’s population is small (around ~1.9 million in 2019, World Bank estimates), but instability and weak policing concentrate risk in particular places (World Bank; Human Rights Watch).

Urban centers with concentrated crime

Major towns concentrate trade, people and informal economies — and where enforcement is thin, they also gather thieves, gangs and trafficking actors. Dense markets and travel hubs make opportunistic street crime and armed robberies more common, while a history of political unrest (notably the 2012 coup) has weakened law-enforcement institutions that might otherwise respond. UNODC analyses in the 2010s flagged urban points, particularly Bissau, as nodes in wider trafficking networks, and that overlap between organized crime and local gangs has real health and safety consequences.

1. Bissau

Bissau, the capital, is the country’s most prominent danger hotspot: it has the densest population, the most visible demonstrations and the highest reported rate of violent incidents. The city concentrates petty crime, armed robberies and periodic political clashes that can turn unpredictable, and its ports and road links make it a natural staging ground for trans-shipment activity noted by UNODC in the 2010s.

Policing is uneven; responders can be slow and investigations seldom reach convictions, which encourages targeting of vulnerable groups and occasional attacks on foreigners. Travel advisories from multiple governments repeatedly single out neighbourhoods of Bissau for heightened caution after protests or high-profile seizures.

Concrete example: security briefings and UNODC-associated reporting in the 2010s documented several notable seizures linked to networks operating through Bissau’s environs, and local human-rights monitors (see Human Rights Watch) have recorded incidents where gang violence followed major drug-busts, sparking short-lived waves of retaliation.

2. Bafatá

Bafatá is a regional administrative center in the interior where banditry and intercommunal disputes periodically escalate into violence. With courts and police stretched thin, market towns around Bafatá have seen clashes over land, trading rights and livestock that sometimes spill into the town itself.

For locals the result is predictable: disrupted market days, families temporarily displaced, and humanitarian actors forced to negotiate access. Reports from the 2010s describe a pattern of livestock theft and localized skirmishes that echo the broader law-enforcement shortfalls outside the capital.

3. Mansôa

Mansôa sits on inland routes linking the interior with Bissau and functions as a transport and market town where highway robberies and ambushes are a recurring problem. The road network funnels traders and commuters through predictable choke-points, and criminal groups exploit those rhythms.

Merchants report changing routes or consolidating travel to daytime convoys; that raises costs and reduces market access for remote producers. Local press accounts in the 2010s documented several highway ambushes near Mansôa that prompted temporary roadblocks by worried residents.

Border and smuggling hotspots

Guinea-Bissau’s porous borders, long mangrove-lined coast and shallow harbors give smugglers many low-cost options for moving drugs, weapons and contraband. Small towns along rivers and the coast become informal transfer points for organized networks identified in UNODC reporting on West Africa in the 2010s.

The practical results: seizures can spark violent reprisals by traffickers, rival groups fight over landing sites, and customs and coast-guard capacity is too limited to patrol every channel. Local communities often pay the price in intimidation, coerced labour and occasional mass arrests that destabilize livelihoods.

4. Cacheu

Cacheu is a river-port town whose mangrove channels and island-like geography make it attractive for small-boat smuggling. The narrow waterways let traffickers move cargoes under the radar of central authorities and mix illicit transfers with legitimate fishing and ferry activity.

Local fishers report pressure from armed groups seeking landing access or protection fees, and regional analyses note patterns of small-boat trafficking that mark Cacheu’s channels as risky. Interceptions and arrests in the 2010s occasionally triggered tit-for-tat violence between rival crews.

5. Quinhamel

Quinhamel’s shallow coastal harbors and informal landing sites make it vulnerable to trans-shipment by small vessels. These pockets of coastline are easy to work from for traffickers using quick landings and local networks to move consignments inland.

The human cost is significant: turf disputes lead to violent confrontations, residents can be coerced into assisting transfers, and security-force raids sometimes provoke short, sharp clashes. Local news reports from the 2010s describe a handful of seizures and follow-on violence that disrupted fishing seasons.

6. Gabú

Gabú, in the east, acts as an interior crossroads where long-distance trafficking routes meet local markets. Limited state reach in the region—sparse police posts and courts with heavy backlogs—creates an environment where control of transit corridors can be contested by armed groups.

The practical outcomes include elevated rates of armed robbery, smuggling-related violence and a general sense that enforcement is inconsistent. Reports from the 2010s linking interior transit corridors to trafficking note Gabú’s importance as a waypoint and the local tensions that follow seizures.

Coastal, island, and southern conflict-prone towns

The southern region and islands face layered risks: spillover from Senegal’s Casamance conflict, limited maritime policing and logistical hurdles that slow any security or humanitarian response. These factors combine so that remote coastal and island towns can be as insecure as urban centres, even if the violence looks different.

Casamance has seen intermittent conflict since the 1980s (1990s–present flare-ups), and when fighting or banditry spikes across the border it increases pressure on towns that lack rapid-response capacity. That means displacement, disrupted fishing and irregular patrols by coast guard units that are often under-resourced.

7. Catió

Catió sits close to the Casamance frontier and is exposed to cross-border movement of fighters and illicit goods. Regional security analyses document episodes in the 2000s–2010s when tension in Casamance translated into armed incidents and spikes in smuggling along the southern coast.

Locals report sudden displacement during flare-ups, interrupted fishing seasons and constrained humanitarian access when authorities concentrate on stabilizing other areas. The mix of smuggling and occasional armed crossings makes Catió a point where external conflict and local criminality meet.

8. Bolama

Bolama, the main town on Bolama Island, illustrates how remoteness itself is a risk factor. Sparse maritime policing and difficult logistics mean that thefts, small-scale violent incidents and illicit landings can go unchallenged for longer than on the mainland.

Consequences include reduced tourism and local commerce, residents exposed to opportunistic criminal groups, and real challenges for medical evacuation or emergency response. Regional reporting about limited coast-guard capacity around the islands underscores how distance amplifies vulnerability.

Summary

- Political shocks (notably the 2012 coup) and weak institutions opened gaps that organized traffickers exploited; UNODC and Human Rights Watch reporting in the 2010s link those dynamics to clear increases in smuggling and related violence.

- Danger in Guinea-Bissau is geographically varied: dense urban centres like Bissau, inland crossroads such as Gabú and Bafatá, riverine ports like Cacheu, coastal trans-shipment points such as Quinhamel, and remote islands like Bolama each present distinct risks.

- Local communities carry the burden: market disruption, displacement, coerced labour and limited access to justice are common consequences—issues documented by the World Bank, UNODC and rights groups.

- Practical takeaways for residents, NGOs and travellers: expect uneven policing, avoid predictable routes after dark, monitor local advisories, and factor in slow emergency response times when planning movement in these towns.

- Improved regional cooperation, better resourcing for coastal and interior policing, and targeted development to reduce reliance on informal economies could lower risks; for further reading see UNODC, the World Bank and Human Rights Watch.