The Sukur Cultural Landscape, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999, is a striking reminder of how some communities in the highlands of northeastern Nigeria have maintained complex social and ritual systems across centuries. That continuity helps explain why customs remain a daily force: they shape identity, create social safety nets, drive festivals and small economies, and mark life’s milestones. Across 250+ ethnic groups and over 500 languages, traditions help people find belonging and practical support—everything from shared labor during harvests to formal naming rites. For a vivid image, imagine a New Yam Festival procession—women carrying yams, drummers leading the way, a priest blessing the first crop—photographs like that often tell the story more directly than words. Traditions in Nigeria remain central to community cohesion, and the ten practices below are grouped into social/family, life‑cycle/ceremonial, festivals/music/dance, and food/dress/crafts to make them easier to explore.

Social & Family Traditions

Kinship, respect for elders, and naming ceremonies structure everyday life across regions. Even with rapid urban growth, these practices persist among Nigeria’s estimated 200M+ people, providing mutual support, moral guidance, and a sense of belonging.

1. Extended family and kinship networks

Extended kinship ties remain a primary social safety net across Nigeria. In many places the household is not just a nuclear family but includes grandparents, siblings, cousins, or in‑laws who pool resources and labor.

Those networks matter in practical ways: remittances from city relatives support rural farming, multiple households share fields and help one another at planting and harvest, and pooled funds pay for schooling or medical bills. Rural household groups often include three generations under one roof, making childcare and eldercare communal responsibilities.

Concrete examples include the Igbo umunna, a kinship council that manages land and lineage obligations, and northern Hausa compound arrangements (often called a zuri’a) where extended families live around a central courtyard to share tasks and security.

2. Respect for elders and hierarchical social roles

Deference to elders is a clear custom: older men and women are consulted on key decisions, arbitrate disputes, and represent continuity with the past. That deference shows up in speech, seating order, and ritual honors.

Councils of elders—formal or informal—still resolve land conflicts, approve marriages, and guide community projects. Traditional rulers such as Yoruba obas or local chiefs lend legitimacy to local initiatives and are often consulted by politicians and businesses seeking community acceptance.

Anthropologists and UNESCO reports note that these roles reduce friction by channeling grievances into recognized procedures; proverbs and ritualized apologies often smooth disputes better than courts in tightly knit places.

3. Naming ceremonies and the social meaning of names

Naming ceremonies mark identity, lineage, and spiritual protection soon after a child’s birth. Names often encode circumstances of birth, family history, or aspirations for the child, and the ritual itself reinforces kin bonds.

In Yoruba culture a child’s name may be given on the seventh or eighth day during an isomoloruko or similar rite, while among the Igbo a ceremony like Igu Afa formally registers a child into the kinship network. These events usually include prayers, libations, and a modest feast.

Common names carry clear meanings—names like Chinedu (God leads) or Olufemi (God loves me)—and even in cities and the diaspora families often maintain these rites as a way to preserve links to lineage and place.

Ceremonial & Life-cycle Traditions

Rites of passage—marriage, funerals, and initiation—are highly visible moments that bind families and communities. They combine ritual, legal implications, and significant economic activity, from bride price talks to the costs of public funerals.

4. Marriage rites and bride price negotiations

Marriage ceremonies remain collective affairs in which extended families negotiate terms and celebrate publicly. Bride price—sometimes called dowry—persists in many areas as a symbolic acknowledgment of kinship ties and obligations rather than a simple sale of a person.

Negotiations involve both families and can include exchanges of goods, kola nuts, and formal speeches. Ceremonies often blend church or mosque services with traditional rites: the couple may marry in a registry, then perform an igba nkwu wine-carrying ritual at an Igbo reception or present kola nuts in a Yoruba engagement.

These practices have real implications: disputes over customary marriages affect inheritance and property rights, and wedding displays signal social standing. Surveys show a wide range in ages at marriage, but customary unions remain common, especially outside major cities.

5. Funerary customs and ancestral veneration

Funerals are major communal events that often last several days and can attract hundreds or even thousands in the case of prominent figures. Wakes, masquerade performances, and memorial feasts honor the dead and reaffirm lineage ties.

Ancestor veneration influences land tenure and inheritance: families maintain shrines, hold annual commemorations, and perform rituals that affirm continuity with forebears. In many towns, a chief’s funeral becomes a public statement of power and history.

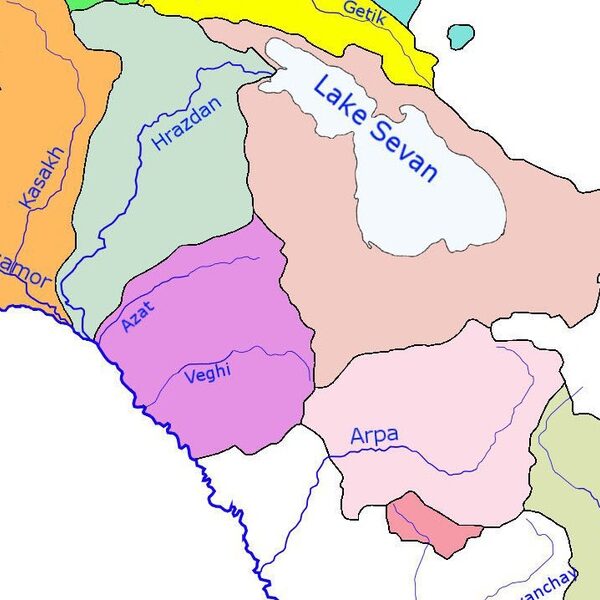

Practices vary: an Igbo funeral may mix Christian burial rites with traditional libations and masquerades, while in some areas elaborate displays and eulogies mark the social contributions of the deceased. Historic sites like Sukur underscore how these practices can be longstanding local institutions.

6. Coming-of-age ceremonies and initiation rites

Many communities observe initiation ceremonies that mark the transition to adulthood and transmit social responsibilities. These rites can include seclusion, instruction in cultural knowledge, and public recognition through age‑grade systems.

Age grades historically organized labor, defense, and civic duties—young men and women moved through stages with defined roles. Rituals teach practical skills, social norms, and oral histories. Some practices have been adapted: risky elements have been replaced with symbolic acts, and community groups now emphasize education and rights.

Debates continue around certain gendered elements, health risks, and consent, but many communities find ways to preserve the instructional and social aspects while modifying procedures for modern life.

Festivals, Music & Dance

Public festivals are theatrical displays of identity, seasonal cycles, and political authority. They attract visitors, support performers and vendors, and act as cultural diplomacy—many are scheduled annually and help sustain local economies.

7. New Yam Festival and harvest celebrations

The New Yam Festival, prominent among the Igbo and echoed in other regions, typically takes place in August or September to thank deities and mark the yam harvest. The first yams are blessed by priests before anyone eats them.

Rituals include yam presentation, pounding demonstrations, masked dances, and communal feasts. The event signals food security for the coming season and offers space for reconciliation and matchmaking. Local vendors and performers see a spike in income during the festival period.

In larger celebrations, thousands attend over several days, making the festival a draw for domestic tourists and a showcase for traditional cooks and craft sellers. That hospitality dynamic helps keep agrarian calendars alive even where farming is no longer everyone’s main livelihood.

8. Durbar, Eyo, and masquerade traditions

Dramatic spectacles like the Durbar of northern emirates and the Eyo processions of Lagos combine pageantry, religion, and history. Durbar events, held after Eid, feature horse cavalcades and royal displays; Eyo processions feature white-clad masqueraders linked to Lagos civic rites.

Masquerades more broadly appear across Yoruba, Igbo, and other cultures, embodying spirits, social critique, or ancestral figures. These performances transmit stories, enforce social norms, and entertain large crowds—some events draw international visitors and media attention.

Major Durbar parades in cities such as Kano can attract thousands, supporting local hotels, transport providers, and artisans who make costumes and regalia. The result: a living cultural economy centered on pageant, music, and movement.

Food, Dress & Craft Traditions

Culinary habits, textiles, and craft traditions communicate origin, status, and hospitality. Several cloth techniques and dishes have become internationally known, while local artisan markets and food stalls are vital to urban livelihoods.

9. Traditional cuisine and communal food practices

Shared meals create culinary identity. Dishes like jollof rice, pounded yam with egusi, and street foods such as suya are central to celebrations, daily life, and regional rivalry—yes, the friendly jollof debates that spark lively conversation across West Africa.

Communal eating at festivals—think yam feasts after harvest—reinforces social bonds, while street‑food markets and small catering businesses supply urban demand and jobs. In Lagos, long-standing suya stands serve as informal hubs for networking and nightlife.

The food sector employs large numbers in informal markets; culinary tourism also draws visitors who want authentic flavors and cooking demonstrations at markets and festivals.

10. Textile, beadwork, and craft traditions

Textiles and crafts carry symbols of status and history while supporting artisans’ livelihoods. Techniques such as Akwete weaving from Abia State and Yoruba Adire resist-dyeing are both practical clothing traditions and creative industries with export potential.

Benin’s bronze casting and beadwork have centuries of history and global resonance; debates about museum restitution show how these pieces matter far beyond local markets. Craft cooperatives, apprenticeship systems, and festival costume production keep technical knowledge alive.

Visitors can often meet weavers or bronze casters in towns like Benin City or Abia State; buying directly from artisans supports local economies and helps preserve skills for future generations.

Summary

These ten practices show how long-standing rituals, social structures, and creative expressions continue to shape life across Nigeria—persisting in rural towns and adapting in crowded cities. They are living institutions that pack social, economic, and symbolic power into everyday actions.

- Traditions sustain social insurance: extended families and elder councils provide practical help and conflict resolution.

- Rites of passage and festivals mark identity and also generate real economic activity for artisans, vendors, and performers.

- Cuisine, textiles, and masquerades transmit history and create livelihoods—some practices are even part of international cultural conversations.

- These customs adapt: communities often keep the symbolic core while changing risky or exclusionary elements to fit modern life.

- Attend a local festival, visit a craft market, or read UNESCO resources to learn respectfully and support cultural continuity.