In 1206, Temüjin was proclaimed Genghis Khan and began building an empire that would reshape Eurasia — a moment that still shapes how the world thinks about Mongolia.

That founding image matters because Mongolia’s past is woven into its present: vast open country, a resilient nomadic society, rich mineral deposits and a surprising role in science and culture attract travelers, scholars and investors. With a population of roughly 3.3 million people spread across about 1.56 million km², Mongolia’s low density produces dramatic contrasts between empty horizons and lively traditional life.

Whether you’re curious about ecotourism on the steppe, the living practice of eagle hunting, dinosaur beds in the Gobi, or the boom-and-bust of mining towns, Mongolia rewards a closer look. The rest of this article highlights eight distinctive things Mongolia is known for, from landscape and wildlife to history and modern change.

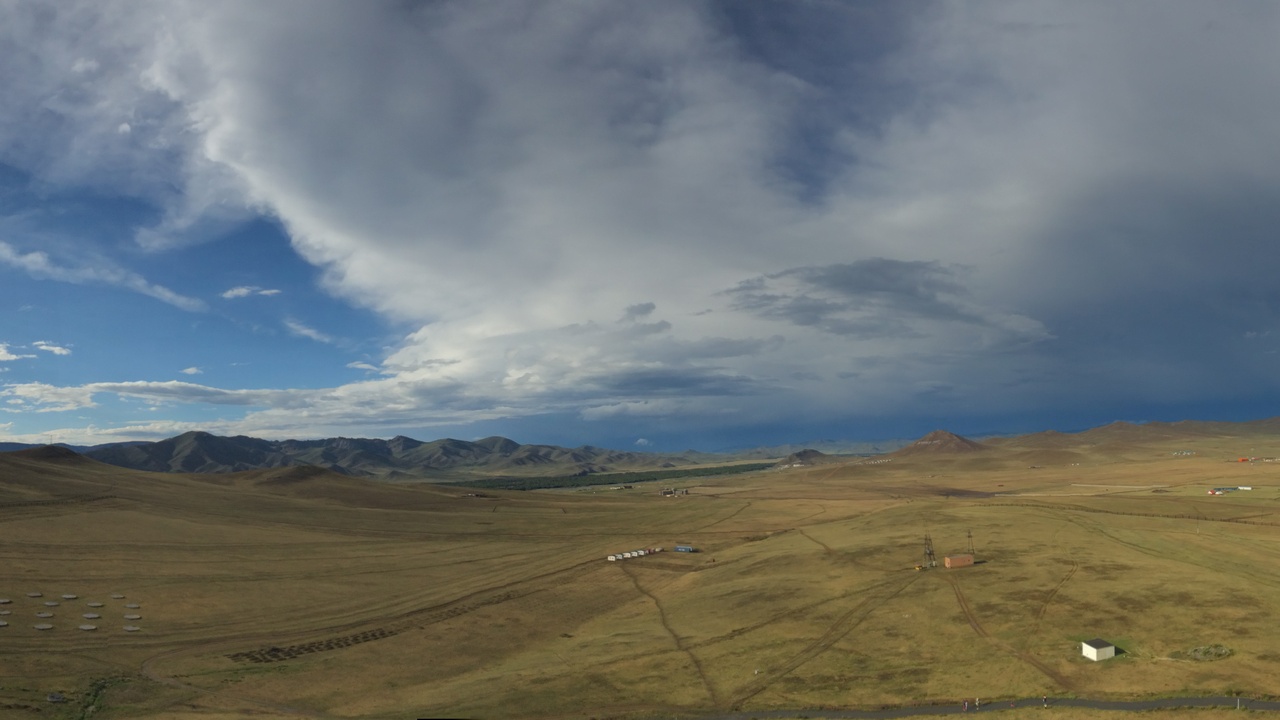

Vast Landscapes and Unique Wildlife

Mongolia’s geography is a defining feature: roughly the size of Alaska at about 1.56 million km², it has one of the world’s lowest population densities. That space shapes livelihoods, from seasonal grazing patterns to long-distance bird migrations and isolated conservation efforts.

For scientists and travelers alike, Mongolia offers contrasts: green, undulating steppe giving way to the arid Gobi Desert, alpine ranges in the west, and scattered wetlands. These ecosystems support specialized wildlife and create economic opportunities tied to pastoralism, eco-tourism and scientific research.

1. The Endless Mongolian Steppe

Mongolia is famed for its vast steppe — an open grassland roughly the size of a small country where herds roam and gers dot the horizon. That open country underpins traditional pastoralism: families move seasonally with flocks of sheep, goats, horses, yaks and camels.

Gers (felt yurts) remain central because they’re portable, insulating and quick to assemble, allowing households to follow pastures. Horse culture is woven into daily life: children learn to ride very young, horses provide transport, and mounted herding remains common. A significant portion of the population still practices some form of pastoralism, making the steppe not just scenery but a living economy and identity.

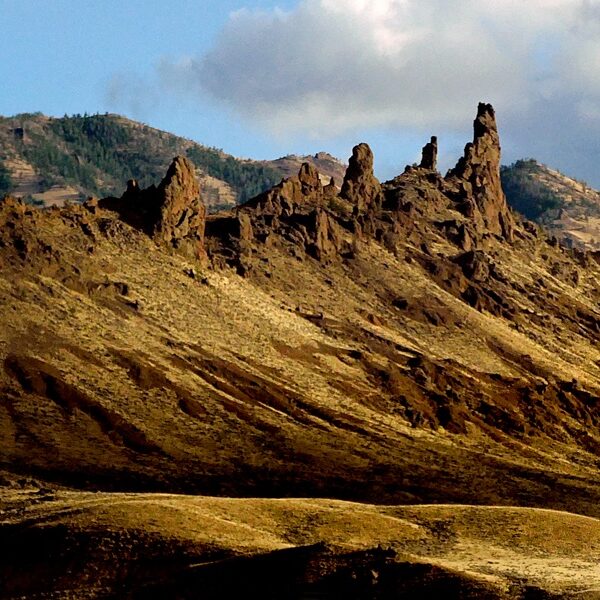

2. The Gobi Desert and its Fossils

The Gobi is a defining landscape of dunes, gravel plains and dramatic rock formations that appear almost lunar at times. It’s also a paleontological treasure trove: 1920s American expeditions led by Roy Chapman Andrews uncovered dinosaur eggs and skeletons, including finds associated with genera like Velociraptor and Protoceratops.

Those discoveries launched decades of scientific work and spurred museum exhibits and fossil tourism. Today researchers still excavate in the Gobi, and small-scale fossil tourism brings visitors to desert oases where hardy plants and specially adapted animals eke out a living.

Living Nomadic Culture and Traditions

Mongolia’s nomadic traditions remain remarkably resilient. Many households still move seasonally between winter and summer pastures, gers remain the primary rural dwelling, and distinctive cultural practices attract scholars and travelers who want to witness living heritage rather than static displays.

From horsemanship to throat singing, these traditions provide livelihoods, social cohesion and identity. The sensory details are vivid: the tang of fermented mare’s milk, the low resonant tones of the morin khuur, and the sight of families arranging winter fodder—small practices rooted in millennia of life on the steppe.

3. Ger Life, Horsemanship, and Eagle Hunting

Mongolia is known for living nomads, mobile gers, and deep horsemanship traditions that begin in childhood. Toddlers often sit on horses, and riding remains a primary skill for herding and long-distance travel across open country.

Ger construction—circular lattice walls, felt coverings and a central smoke hole—makes seasonal moves practical. In the far west, Kazakh Mongols keep the ancient craft of eagle hunting alive; trained golden eagles hunt foxes and are showcased at festivals in Bayan-Ölgii province.

These practices sustain rural incomes through tourism and local trade, and they keep cultural knowledge living rather than museum-bound.

4. Naadam, Music, and Intangible Heritage

Naadam, held every July, is Mongolia’s flagship festival celebrating wrestling, horse racing and archery—the “Three Manly Games.” Large public events in Ulaanbaatar and local competitions across aimags draw participants of all ages.

Musical forms like throat singing (khöömei) and instruments such as the morin khuur (horsehead fiddle) carry centuries of narrative. Several traditions enjoy international recognition and UNESCO attention, and the festival season keeps those art forms in active practice.

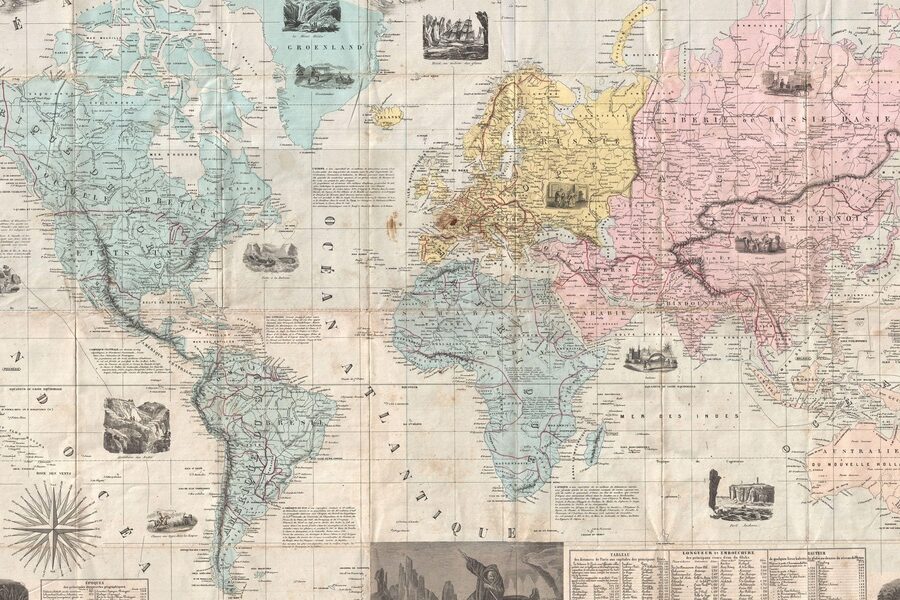

A Compelling Historical Legacy

Mongolia’s history resonates far beyond its borders. From Temüjin’s unification in 1206 to 20th-century revolutions and a 1990 democratic shift, historical currents have shaped national identity and global perceptions of the country.

Monasteries, imperial routes and archaeological sites connect contemporary Mongolia to a layered past, while museums and monuments turn that past into tourism and civic memory.

5. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire

Mongolia is widely known internationally because of Genghis Khan and the 13th-century empire he forged after 1206. Over a few decades the Mongol state expanded across Eurasia, influencing trade, diplomacy and military practice.

Mongol innovations—relay stations for mounted messengers and highly mobile mounted archery units—helped secure long-distance trade routes and affected administrative practices in successor states. Today Genghis Khan is a central national symbol, visible in large statues near Ulaanbaatar and in museums at sites like Kharkhorin and Erdene Zuu.

6. Buddhism, Monasteries, and Cultural Revival

Tibetan Buddhism shaped Mongolia from the 16th century onward, with monasteries serving as learning centers and social hubs. Soviet-era purges in the 1930s decimated many institutions, but religious and cultural revival since the 1990s has restored monasteries and rituals.

Erdene Zuu near Kharkhorin stands as a visible example of restoration and pilgrimage. The revival of monastic festivals and the reopening of temples have bolstered cultural tourism and renewed spiritual life across the country.

Modern Mongolia: Resources, Cities, and Tourism

When people ask “what is mongolia known for”, attention often turns to its mineral wealth, a rapidly growing capital and a tourism industry built around nomadic experiences. Mining, urban migration and travel have reshaped the economy in recent decades.

Ulaanbaatar concentrates roughly 40–50% of the population (about 1.3–1.6 million people), while mining projects attract foreign investment and drive infrastructure projects—often amid debates over fair revenue distribution and environmental impact.

7. Mining, Natural Resources, and the Modern Economy

Mongolia is known for significant mineral wealth: coal, copper and gold top the list. Large projects like the Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold mine have drawn major foreign partners and become central to national economic planning.

Mining accounts for an estimated 20–30% of GDP and a very large share of exports—figures vary year to year but mining dominates trade balances. That dependence brings tradeoffs: infrastructure and jobs, but also debates over governance, environmental management and how communities benefit from resource wealth.

Major players such as Rio Tinto (through its stake in Turquoise Hill) illustrate the scale of foreign involvement, while coal extraction in southern aimags remains a significant regional employer.

8. Ulaanbaatar, Urban Life, and Growing Tourism

Ulaanbaatar is the focal point of modernization and challenge: roughly half the country’s people live there, and the city hosts government institutions, cultural museums and large monuments like the Genghis Khan complex outside the city.

Urban realities include severe winter air pollution and sprawling ger districts where newcomers live in traditional gers without urban services. At the same time, museums, festivals and ger-camp tourism create opportunities—pre-2020 Mongolia attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors annually who sought Gobi tours, steppe stays and Naadam events.

Travel operators now blend modern comforts with authentic experiences: overnight ger camps on the steppe, guided paleontology excursions in the Gobi, and cultural tours around Kharkhorin and Erdene Zuu.

Summary

Mongolia stands out for contrasts: an empire that reshaped Eurasia began in 1206, yet today the country balances living nomadic culture, vast empty lands and a resource-driven modern economy centered on Ulaanbaatar. Its landscapes—steppe and Gobi—support unique wildlife, ongoing paleontological discovery and resilient human traditions like ger life, horsemanship and Naadam festivities.

At the same time, mining projects such as Oyu Tolgoi and rapid urban migration have made modernization visible and controversial. Cultural revival in monasteries and international interest in festivals and music show that history and identity remain central to Mongolia’s future.

- Vast space and low population density give Mongolia distinctive ecological and cultural dynamics.

- Living nomadic practices—gers, horsemanship and eagle hunting—connect past and present.

- Genghis Khan’s legacy, Gobi fossils and Buddhist revival are key reasons Mongolia attracts study and tourism.

- Consider visiting or supporting ethical tourism and conservation programs to experience Mongolia responsibly.