Kiribati spreads across the central Pacific as a chain of low-lying atolls and islands, and its language landscape reflects that island geography. Local speech varieties have developed through long-distance voyaging, inter-island ties, and centuries of community life.

There are 21 Dialects in Kiribati, ranging from Abaiang to Tamana. For each entry the data is organized by Region / islands,Speakers,Key features so you can quickly see where a dialect is spoken, how many people use it, and what sets it apart — you’ll find below.

How different are these dialects from one another?

Differences are mostly in pronunciation, some vocabulary, and small grammatical shifts; mutual intelligibility is generally high between neighboring islands but can drop across more distant atolls. The list below highlights key features that help gauge how distinct each variety is.

Will a visitor be understood across Kiribati?

Yes, standard Kiribati (Gilbertese) and closely related dialects allow basic communication across most islands, but visitors should expect local words and pronunciations to vary; regional speakers are usually happy to clarify or switch to a more commonly understood form.

Dialects in Kiribati

| Dialect | Region / islands | Speakers | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Tarawa | South Tarawa (urban lagoon islets) | 63,000 | Urban standard; many English loans; fast, mixed dialect features |

| North Tarawa | North Tarawa (central atoll) | 6,000 | Conservative pronunciations; slower tempo; traditional vocabulary |

| Abaiang | Abaiang atoll | 4,000 | Conservative phonology; distinct stress patterns; local lexicon |

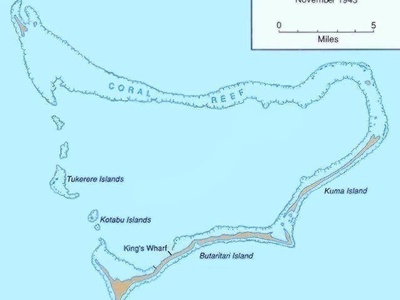

| Butaritari | Butaritari island (northern group) | 3,000 | Northern phonology; unique intonation; localized words |

| Makin | Makin island (northern group) | 2,000 | Northern consonant patterns; some archaisms; local terms |

| Marakei | Marakei island (central-north) | 2,000 | Distinct vowels; conservative grammar; island idioms |

| Maiana | Maiana atoll | 1,800 | Blended Tarawa-northern traits; some local lexicon |

| Abemama | Abemama island (central) | 3,100 | Central phonology; unique lexical items; clear articulation |

| Kuria | Kuria islands (central) | 1,000 | Conservative forms; local loanwords; compact phonology |

| Aranuka | Aranuka islands (central) | 1,200 | Central features; distinct intonation; local vocabulary |

| Nonouti | Nonouti island (central-south) | 5,500 | Southern-leaning vocabulary; vowel tendencies; idiomatic speech |

| Tabiteuea North | Tabiteuea (north) island | 3,800 | Southern phonology; different pronouns; local lexicon |

| Tabiteuea South | Tabiteuea (south) island | 3,500 | Strong southern traits; unique vocabulary; speech rhythm |

| Beru | Beru island (southern group) | 3,200 | Southern vowel shifts; unique idioms; slower delivery |

| Nikunau | Nikunau island (southern) | 1,800 | Distinct phonetic shifts; local vocabulary; archaisms |

| Onotoa | Onotoa island (southern) | 1,700 | Southern consonant patterns; unique lexical items |

| Tamana | Tamana island (southern) | 450 | Very localized lexicon; conservative forms; slow speech |

| Arorae | Arorae island (southern) | 900 | Isolated features; conservative vocabulary; distinct rhythm |

| Banaba | Banaba (Ocean Island) | 300 | Distinct local terms; some phonological divergence |

| Northern Gilbertese | Northern Gilbert Islands (general) | 20,000 | Shared northern traits; lexical differences from south; intonation patterns |

| Southern Gilbertese | Southern Gilbert Islands (general) | 25,000 | Southern vowel shifts; distinct pronouns and idioms; archaisms |

Images and Descriptions

South Tarawa

South Tarawa speech is the de facto broadcast and school standard used nationwide. It mixes island features, borrows many English words, and is widely intelligible; urban slang and rapid speech set it apart from outer-island varieties.

North Tarawa

North Tarawa preserves older pronunciations and many traditional words. Speakers are mutually intelligible with South Tarawa but retain clearer conservative speech patterns and local expressions, often perceived as more “island” than urban Tarawa.

Abaiang

Abaiang speech keeps several conservative phonetic traits and island-specific vocabulary. Intelligibility with Tarawa is high, but Abaiang speakers often recognize each other by pronunciation and retained older forms.

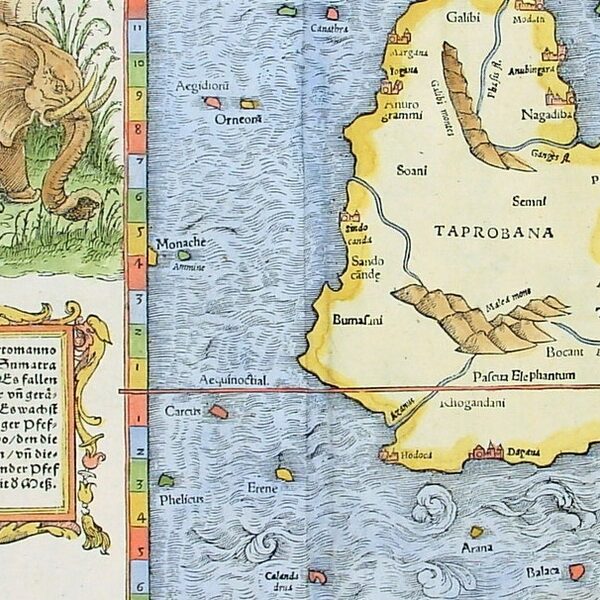

Butaritari

Butaritari represents the northern Gilbertese sound system with its own intonation and some unique lexical items. It remains mutually intelligible with other Gilbertese dialects but sounds noticeably northern to listeners from the south.

Makin

Makin’s variant shares northern features (consonant choices, archaisms) and island-specific vocabulary. Visitors notice a slightly different rhythm and some words unfamiliar to southern speakers, though mutual understanding is strong.

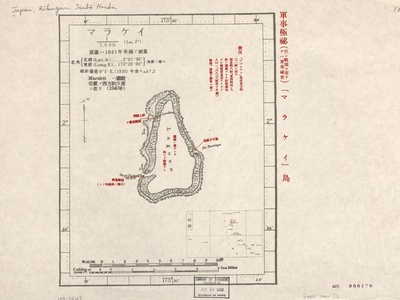

Marakei

Marakei speech shows distinct vowel qualities and some conservative grammatical forms. It is readily understood by other Gilbertese speakers but preserves local idioms and expressions people identify with the island.

Maiana

Maiana’s dialect blends Tarawa features with northern elements, producing a recognizable local flavor. Its vocabulary and pronunciation are close enough to be mutually intelligible with minimal difficulty.

Abemama

Abemama speech sits near the central cluster of dialects with a few island-specific words and crisp pronunciation. Visitors find it similar to Tarawa but with notable local expressions and speech rhythms.

Kuria

Kuria preserves older lexical items and conservative phonological patterns. The dialect is mutually intelligible but marked by island-specific vocabulary and slightly distinct pronunciation.

Aranuka

Aranuka’s dialect fits the central group but shows its own intonation patterns and local words. Comprehension with neighboring islands is strong, with subtle pronunciation cues identifying Aranuka speakers.

Nonouti

Nonouti leans toward southern phonology with certain vowel tendencies and idiomatic expressions. It remains mutually intelligible with Tarawa but carries a recognizably southern island character in speech and phrasing.

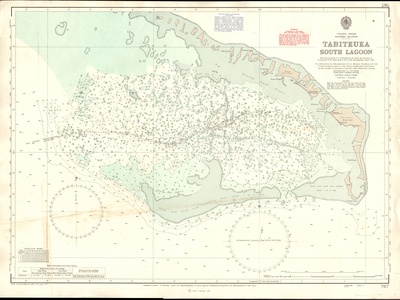

Tabiteuea North

Tabiteuea North displays southern-type sounds and some pronoun and lexical differences from northern dialects. Mutual intelligibility is generally good but listeners note distinct southern features.

Tabiteuea South

Tabiteuea South is a clear southern variant with characteristic vocabulary and speech rhythm. It can sound notably different to northern listeners while remaining largely understandable.

Beru

Beru’s dialect shows southern vowel patterns, distinctive idioms and a measured speech tempo. It is mutually intelligible with other Gilbertese dialects but often immediately recognized as southern.

Nikunau

Nikunau preserves several distinctive phonetic shifts and older words, giving it a distinct southern island identity. Intelligibility remains high, though some terms are unfamiliar outside the south.

Onotoa

Onotoa speech shares many southern features, including consonant patterns and island-specific words. It’s intelligible to other Kiribati people, and is noted for its local color and phrasing.

Tamana

Tamana has a very localized variety with conservative forms and many island-specific expressions. Small population keeps features tight-knit; outsiders understand most speech but notice many Tamana-only words.

Arorae

Arorae speech reflects long isolation with conservative vocabulary and a distinct speech rhythm. It is intelligible to other Gilbertese speakers but contains unique words and pronunciations.

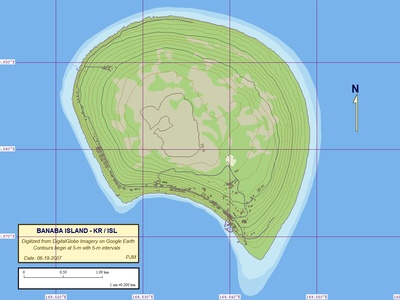

Banaba

Banaba variety shows local lexical and phonological traits that set it apart; historically linked to Gilbertese but with island-specific forms. It remains broadly intelligible to Kiribati speakers but is often recognized as Banaban speech.

Northern Gilbertese

Northern Gilbertese groups (Butaritari, Makin, Marakei, Abaiang, etc.) share phonological and lexical features distinguishing them from southern islands. Mutual intelligibility with other dialects is high, though northern speech sounds distinct.

Southern Gilbertese

Southern Gilbertese (Beru, Nikunau, Onotoa, Tamana, Arorae, etc.) shares southern phonological traits and unique vocabulary. Southern forms may sound noticeably different but remain largely intelligible to northern speakers.