Mexico is home to a rich tapestry of languages tied to distinct communities, histories, and regions, and that diversity shapes much of the country’s cultural life. Listening to local speech and place names reveals layers of identity you won’t find in official Spanish alone.

There are 59 Indigenous Languages in Mexico, ranging from Akateko to Zoque. For each entry I list Speakers (number),States/regions,Family so you can quickly see how many people speak it, where it’s used, and its linguistic family — details you’ll find below.

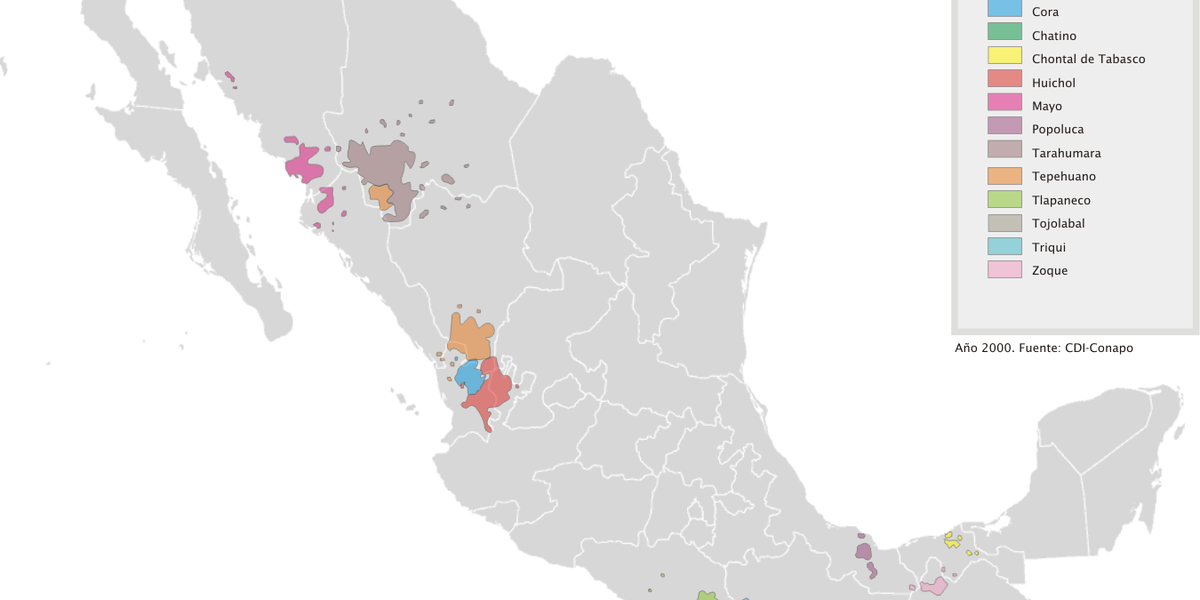

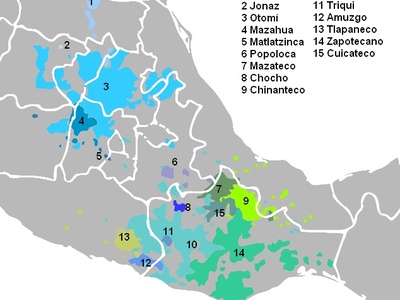

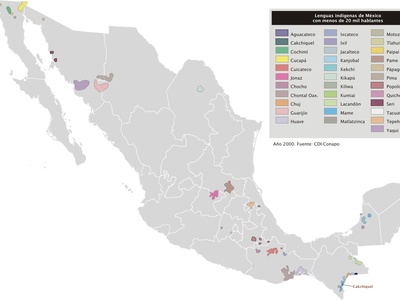

How are these languages distributed across Mexico?

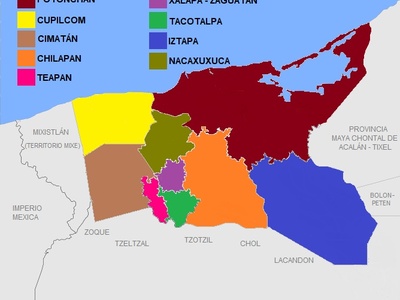

Most indigenous languages cluster in southern and central states: Oaxaca, Chiapas, Yucatán/Peninsula, Puebla, Veracruz and Guerrero host many distinct tongues, while northern regions have fewer but still important languages; families like Mayan, Oto‑Manguean, Uto‑Aztecan and Mixe–Zoque show different geographic patterns that reflect migration and local history.

How reliable are the speaker counts and where do they come from?

Speaker numbers usually come from national censuses and linguistic surveys (INEGI, INALI, Ethnologue), but they vary by year and methodology — some are self‑reported, others use fluency tests — so treat figures as approximations and check the source and date for the most accurate picture.

Indigenous Languages in Mexico

| Language | Speakers (number) | States/regions | Family |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nahuatl | 1,651,958 | Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Guerrero | Uto-Aztecan |

| Maya | 774,755 | Yucatán, Quintana Roo, Campeche | Mayan |

| Tseltal | 589,144 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Tsotsil | 550,274 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Mixtec | 526,593 | Oaxaca, Guerrero, Puebla | Oto-Manguean |

| Zapotec | 490,845 | Oaxaca | Oto-Manguean |

| Otomí | 298,861 | Hidalgo, State of Mexico, Querétaro | Oto-Manguean |

| Totonac | 256,444 | Veracruz, Puebla | Totonacan |

| Chol | 254,715 | Chiapas, Campeche, Tabasco | Mayan |

| Mazatec | 237,145 | Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz | Oto-Manguean |

| Huastec | 168,729 | San Luis Potosí, Veracruz | Mayan |

| Mazahua | 153,797 | State of Mexico, Michoacán | Oto-Manguean |

| Chinantec | 144,394 | Oaxaca, Veracruz | Oto-Manguean |

| Mixe | 140,046 | Oaxaca | Mixe-Zoquean |

| Purépecha | 142,371 | Michoacán | Isolate |

| Tlapanec | 147,615 | Guerrero | Oto-Manguean |

| Tarahumara | 91,554 | Chihuahua | Uto-Aztecan |

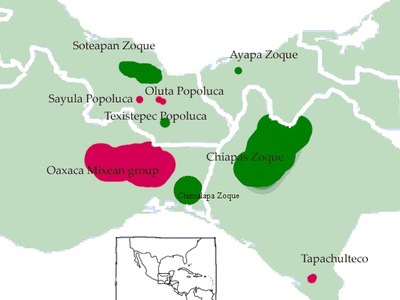

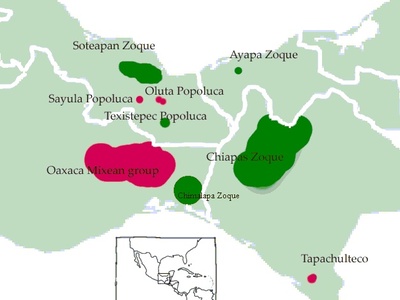

| Zoque | 74,018 | Chiapas, Oaxaca, Veracruz | Mixe-Zoquean |

| Amuzgo | 60,575 | Guerrero, Oaxaca | Oto-Manguean |

| Tojolabal | 66,953 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Huichol | 60,263 | Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango | Uto-Aztecan |

| Popoluca de la Sierra | 36,113 | Veracruz | Mixe-Zoquean |

| Cora | 33,226 | Nayarit, Jalisco | Uto-Aztecan |

| Triqui | 29,545 | Oaxaca | Oto-Manguean |

| Yaqui | 19,376 | Sonora | Uto-Aztecan |

| Huave | 18,827 | Oaxaca | Isolate |

| Popoloca | 17,274 | Puebla | Oto-Manguean |

| Mayo | 39,618 | Sinaloa, Sonora | Uto-Aztecan |

| Tepehuano del Sur | 37,549 | Durango, Nayarit, Zacatecas | Uto-Aztecan |

| Tepehua | 9,990 | Veracruz, Hidalgo, Puebla | Totonacan |

| Chatino | 52,076 | Oaxaca | Oto-Manguean |

| Q’anjob’al | 10,851 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Mam | 8,861 | Chiapas, Campeche, Quintana Roo | Mayan |

| Chontal de Oaxaca | 4,959 | Oaxaca | Tequistlatecan |

| Pame | 11,627 | San Luis Potosí | Oto-Manguean |

| Chontal de Tabasco | 43,850 | Tabasco | Mayan |

| Guarijío | 2,844 | Chihuahua, Sonora | Uto-Aztecan |

| Chuj | 2,136 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Akateko | 1,478 | Chiapas, Campeche, Quintana Roo | Mayan |

| Jakalteko | 637 | Chiapas, Campeche | Mayan |

| Q’eqchi’ | 1,365 | Chiapas, Campeche | Mayan |

| Tepehuano del Norte | 9,855 | Chihuahua | Uto-Aztecan |

| Lacandon | under 1,000 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Seri | 989 | Sonora | Isolate |

| K’iche’ | 1,268 | Chiapas, Campeche, Quintana Roo | Mayan |

| Paipai | 221 | Baja California | Yuman |

| Kumiai | 383 | Baja California | Yuman |

| Cucapá | 198 | Baja California, Sonora | Yuman |

| Pima Bajo | 845 | Chihuahua, Sonora | Uto-Aztecan |

| Ixcatec | 195 | Oaxaca | Oto-Manguean |

| Matlatzinca | 1,245 | State of Mexico | Oto-Manguean |

| Tlahuica | 2,257 | State of Mexico | Oto-Manguean |

| Kiliwa | 46 | Baja California | Yuman |

| Chocholtec | 814 | Oaxaca | Oto-Manguean |

| Ixil | 474 | Campeche, Quintana Roo | Mayan |

| Kikapú | 118 | Coahuila | Algic |

| Teko | 230 | Chiapas | Mayan |

| Oluteco | 22 | Veracruz | Mixe-Zoquean |

| Ayapaneco | 12 | Tabasco | Mixe-Zoquean |

Images and Descriptions

Nahuatl

The most widely spoken indigenous language in Mexico, famously the language of the Aztec Empire. It has given the world words like “chocolate,” “avocado,” and “tomato.” It is recognized as a national language with many distinct modern varieties.

Maya

The language of the ancient Maya civilization, still spoken by hundreds of thousands in the Yucatán Peninsula. It is the second most spoken indigenous language in Mexico and has a rich literary tradition extending from pre-Columbian times to today.

Tseltal

A major Mayan language spoken in the highlands of Chiapas. Closely related to Tsotsil, it is part of a vibrant cultural region where indigenous languages are a fundamental part of daily life and local governance in many communities.

Tsotsil

Another prominent Mayan language from the Chiapas highlands. Tsotsil speakers are known for their distinctive traditional clothing and strong community identity. The language is central to the social and religious life in municipalities like San Juan Chamula.

Mixtec

A large complex of related languages spoken across the “La Mixteca” region. Known for its intricate tonal system, where the pitch of a word can change its meaning, and for its ancient pictographic writing system found in historical codices.

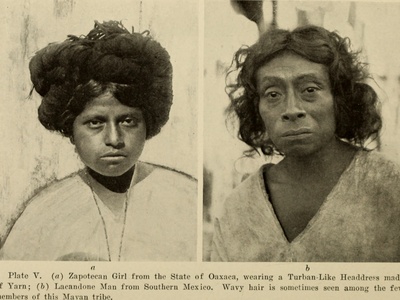

Zapotec

A major language group of Oaxaca, comprising over 50 distinct varieties, some of which are not mutually intelligible. Zapotec languages are known for their complex sound systems and have been written since at least 500 B.C.

Otomí

Spoken in the central highlands, Otomí is a diverse language group with a long history. It is a tonal language, and some varieties have a unique whistled speech used for long-distance communication. Efforts are underway to revitalize its use.

Totonac

Spoken in east-central Mexico, particularly around the ancient city of El Tajín. The language is famous for its complex grammar and sounds. The “Voladores de Papantla” ritual has its roots in Totonac culture, which remains vibrant.

Chol

A Mayan language closely related to Chontal of Tabasco and the language of the Palenque inscriptions. Spoken in the northern part of Chiapas, it plays a vital role in the cultural identity of the Chol people, who are active in its preservation.

Mazatec

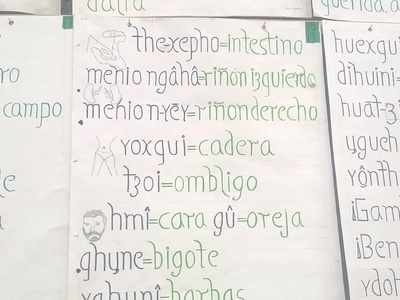

Best known for its complex whistled speech, which allows speakers to communicate across the deep valleys of the Sierra Mazateca. This tonal language has a rich spiritual tradition and is integral to the identity of the Mazatec communities.

Huastec

A Mayan language geographically separated from the rest of the family in southeastern Mexico. Spoken in the Huasteca region, it is the remnant of a much wider Mayan presence in the past and has coexisted with other cultures for centuries.

Mazahua

Primarily spoken in the State of Mexico, west of Mexico City. The Mazahua people are known for their intricate textiles and strong community ties. The language is tonal and has a complex sound system that includes ejective consonants.

Chinantec

A group of languages from northern Oaxaca famous for its highly complex system of tone and whistled speech. Some varieties have as many as seven distinct tones, making it one of the most tonally complex language families in the world.

Mixe

Spoken in the highlands of Oaxaca, Mixe is related to Zoque and the language of the ancient Olmecs. The Mixe people have a strong cultural identity and have been successful in promoting language use through community-based educational initiatives.

Purépecha

A language isolate, meaning it has no known relatives. Spoken around Lake Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, it was the language of the powerful Tarascan State, a rival of the Aztec Empire. The language and culture are a source of great pride.

Tlapanec

Spoken in the mountainous region of Guerrero, Tlapanec is a tonal language. Once thought to be an isolate, it is now classified as part of the Oto-Manguean family. It is the primary language in several municipalities.

Tarahumara

The language of the Rarámuri people of the Copper Canyon, known for their long-distance running abilities. The language is central to their culture and worldview, which is deeply connected to the rugged landscape of the Sierra Tarahumara.

Zoque

A language family descended from the language of the Olmec civilization. Zoque is spoken in distinct regions and faces challenges from language shift, but community efforts are in place to preserve its rich cultural heritage.

Amuzgo

A tonal language spoken in the Costa Chica region of Guerrero and Oaxaca. The Amuzgo people are renowned for their traditional backstrap loom weaving. The language is an integral part of their vibrant artistic and cultural life.

Tojolabal

A Mayan language spoken in eastern Chiapas. Tojolabal has a distinct grammatical feature called “inter-subjectivity,” reflecting a worldview that emphasizes community and shared experience. It remains the primary language in many of its communities.

Huichol

The language of the Wixárika people, known for their intricate yarn paintings and beadwork. The language is central to their complex ceremonial and religious life, which has been remarkably well-preserved in the Sierra Madre Occidental.

Popoluca de la Sierra

Also known as Soteapanec, this is a Mixe-Zoquean language spoken in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas of Veracruz. Though its speaker base is declining, it holds the linguistic heritage of one of Mexico’s most ancient language families.

Cora

Spoken in the mountains of Nayarit, Cora is a Uto-Aztecan language with a rich ceremonial tradition. The language is deeply intertwined with the Cora people’s religious practices and their unique understanding of the world.

Triqui

A language from western Oaxaca known for its extremely complex tonal systems; the Chicahuaxtla variety has one of the highest numbers of tones of any language. The Triqui people have a strong presence both in Oaxaca and as migrants in other parts of Mexico.

Yaqui

The language of the Yaqui people (Yoeme) of Sonora and Arizona. The Yaqui have a history of fierce resistance to assimilation, and their language is a vital symbol of their cultural sovereignty and identity, especially in their traditional ceremonies.

Huave

Spoken by the Ikoots people on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca, this language is an isolate with no known relatives. The Huave are known as the “Sea People,” and their language reflects a deep connection to the coastal environment.

Popoloca

An Oto-Manguean language spoken in southern Puebla. It is closely related to Mazatec but is a distinct language. Popoloca communities are working to maintain their language and culture in the face of pressure from Spanish.

Mayo

Closely related to Yaqui, this Uto-Aztecan language is spoken along the coastal plains of southern Sonora and northern Sinaloa. The Yoreme (Mayo) people have a rich cultural tradition, and their language is a key component of their identity.

Tepehuano del Sur

Spoken in the Sierra Madre Occidental, it is part of the Tepiman branch of the Uto-Aztecan family. The O’dam (Tepehuano) people have maintained a strong connection to their language and traditional lands.

Tepehua

A group of three languages closely related to Totonac, spoken in the Eastern Sierra Madre. The name “Tepehua” comes from Nahuatl and means “mountain owner.” The language is considered endangered.

Chatino

A group of Oto-Manguean languages spoken in the southern highlands of Oaxaca. Like their Zapotec and Mixtec neighbors, Chatino languages are tonal and have complex grammars. They are central to the identity of the Chatino communities.

Q’anjob’al

A Mayan language spoken primarily in Guatemala but also by communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Many speakers are refugees or descendants of refugees from the Guatemalan Civil War who have established permanent communities in Mexico.

Mam

Like Q’anjob’al, Mam is a major Mayan language of Guatemala with a significant speaker population in Mexico, particularly in Chiapas. These communities maintain their language and cultural traditions far from their ancestral homelands.

Chontal de Oaxaca

A language isolate (or small family with its extinct relative) spoken in the southern Oaxaca mountains. It is highly endangered and should not be confused with Chontal of Tabasco, which is a Mayan language.

Pame

An Oto-Manguean language spoken in the arid region of San Luis Potosí. The Xi’úi (Pame) people are the northernmost members of this language family. The language is endangered, with most speakers being elderly.

Chontal de Tabasco

A Mayan language spoken in the wetlands of Tabasco. Unlike its highland Mayan relatives, it has a simpler grammar and lacks tones. The language is a key part of the identity of the Yokot’anob (Chontal) people.

Guarijío

A Uto-Aztecan language spoken in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental. It exists in two main dialects, Highland and Lowland, and is closely related to Tarahumara. The language is considered endangered.

Chuj

Another Mayan language with its main population in Guatemala, Chuj speakers in Mexico are largely concentrated in refugee communities in Chiapas. They have worked to preserve their language and culture while adapting to their new home.

Akateko

A Mayan language, also primarily from Guatemala, with refugee communities in Mexico. These communities have shown remarkable resilience in maintaining their language and cultural practices across international borders.

Jakalteko

Also known as Popti’, this is a Mayan language from Guatemala with a small but established speaker community in Mexico. Like other cross-border Mayan groups, they work to preserve their unique linguistic and cultural heritage.

Q’eqchi’

A major Mayan language of Guatemala and Belize with a growing number of speakers in Mexico, primarily in refugee settlements. The language is known for being grammatically conservative and is used actively in daily life.

Tepehuano del Norte

Spoken by the Ódami people in southern Chihuahua, this language is a counterpart to the Southern Tepehuano of Durango. Though related, the two are not mutually intelligible. The language remains integral to community life.

Lacandon

A critically endangered Mayan language spoken by the Hach Winik people in the Lacandon Jungle of Chiapas. With very few speakers left, it is the focus of intense documentation and revitalization efforts to save it from extinction.

Seri

A language isolate spoken by the Comca’ac people on the coast of Sonora. The language is known for its complex sound system and its deep connection to the desert and sea environment, encoding vast traditional ecological knowledge.

K’iche’

The most widely spoken Mayan language in Guatemala, with a small population of speakers in Mexico, mostly in refugee camps. The language of the famous Popol Vuh, it holds a prestigious place in Mayan culture.

Paipai

A highly endangered Yuman language of northern Baja California. It is part of the “Yuman Cordon,” a chain of related languages spoken across Baja and into the US. Efforts are underway to document the language from its few remaining elder speakers.

Kumiai

A Yuman language spoken on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Kumiai communities are actively working on language revitalization projects, including language nests and classes, to pass the language on to younger generations.

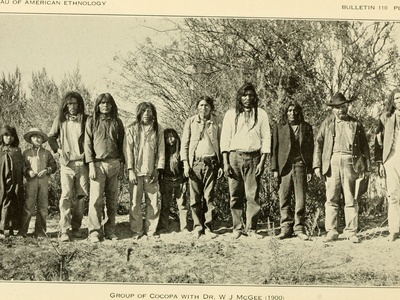

Cucapá

A critically endangered Yuman language spoken by the Cocopah people near the Colorado River Delta. The language is closely tied to the river’s ecosystem, and revitalization efforts are crucial for its survival.

Pima Bajo

The language of the O’ob people, spoken in the Sierra Madre Occidental. It is a member of the Tepiman branch of Uto-Aztecan, and though endangered, it is a repository of the region’s history and culture.

Ixcatec

A critically endangered Oto-Manguean language spoken in the single village of Santa María Ixcatlán, Oaxaca. With only a handful of elderly speakers remaining, it is one of Mexico’s most threatened languages.

Matlatzinca

An endangered Oto-Manguean language spoken in a single community in the State of Mexico. It is closely related to Tlahuica. Community and government initiatives are working to promote its use among younger generations.

Tlahuica

Also known as Ocuilteco, this is a highly endangered Oto-Manguean language from the State of Mexico. Spoken in just a few villages, it is the focus of revitalization efforts aimed at preventing its disappearance.

Kiliwa

A moribund Yuman language of northern Baja California with only a few elderly speakers left. Linguists consider it the most divergent of the Yuman languages and are working to document it before it falls silent.

Chocholtec

A severely endangered Oto-Manguean language of the Mixteca region of Oaxaca. Also known as Ngigua, the language is no longer being passed on to children, but there is growing interest in revitalization among the community.

Ixil

A Mayan language from the Cuchumatanes mountains of Guatemala, spoken by refugee communities in Mexico. Despite displacement, the Ixil people have maintained a strong cultural identity in which their language plays a central role.

Kikapú

An Algonquian language spoken by the Kickapoo tribe, who migrated to Mexico from the Great Lakes region of the US in the 19th century. They are a federally recognized tribe in both the US and Mexico, maintaining their unique language and traditions.

Teko

A Mayan language, also known as Motocintleco, spoken in a small area near the Guatemala border. It is closely related to Mam and is severely endangered, with very few speakers remaining in Mexico.

Oluteco

A Mixean language on the brink of extinction, spoken in the municipality of Oluta, Veracruz. With only a few elderly speakers left, urgent documentation efforts are underway to preserve a record of this language.

Ayapaneco

A critically endangered Mixe-Zoquean language from Tabasco, famously reported to have had only two remaining speakers who refused to talk to each other. While an exaggeration, the language is moribund and the focus of revitalization efforts.